Dr. Bennett

Dr. Bennett of Shreveport, Louisiana (probably born in England) was often credited as the inventor of thimble-rig, which isn’t correct. He was, however, one of the first and certainly one of the best-known thimble worker to have worked the scam in the United States. He made a fortune playing the game on the Red and Mississippi River steamboats, where he was known as the King of the Thimbles and the Napoleon of the Thimble-Riggers . In the early 1840’s, the Doctor and a group of his disciples created such havoc among the bucolic sports of Georgia, Alabama, Tennessee and Mississippi that stringent laws were passed in those states specifically prohibiting the game.

Dr. Bennett claimed that thimble-rig had been his principal source of income since boyhood, which meant that he must have been performing the scam since before 1800. In 1845, at the age of seventy, Bennett was a kindly-appearing older gentleman with snow white hair and a disarming trick of peering over his spectacles and saying, “Sometimes, my boy, I am very severe, then again not quite so sly.”

He played with thimbles and a moistened paper ball, and was famous for a ruse in which a tiny triangle of paper was glued to the inside of one of the thimbles. Whenever called for, he would turn that thimble toward the sucker and pull back slightly which caused the tiny piece of paper to be exposed for a short time. The sucker would assume that the ball was under that thimble.

James “Umbrella Jim” Miner

One of the early “kings” of the Mississippi shell game artists, James Miner was known variously as Umbrella Jim and as the Poet Gambler . He was called “Umbrella Jim” for his habit of beginning his con game under an umbrella–rain or shine, indoors or out. He was called the Poet Gambler for his famous doggerel that he used to accompany his shell game:

“A little fun, just now and then,

Is relished by the best of men.

If you have nerve, you may have plenty;

Five draws you ten, and ten draws twenty.

Attention given, I’ll show to you,

How ‘Umbrella’ hides the peek-a-boo.

Select your shell, the one you choose;

If right, you win; if not, you lose;

The game itself is lots of fun,

Jim’s chances, though, are two to one;

And I tell you your chance is slim

To win a prize from Umbrella Jim.”

–“Umbrella Jim” Miner

William B. “Lucky Bill” Thornton (182?- 1858)

Bret Harte may have based his fictional gambler Jack Hamlin on “Lucky Bill,” the most notorious of the California gold rush “sure-thing” gamblers. Thornton was born in Chenango County, New York. A tall broad-shouldered man with curly black hair and large gray eyes, Thornton was considered quite a ladies man, once traveling with a “harum” of three young women.

“Lucky Bill” joined a wagon train to California in 1849, and by the time he reached the Pacific Slope he had most of the money of his fellow travelers. Thornton operated a shell game played with little metal cups shaped like half-walnut shells and a blackened cork pea. He performed on a tray suspended from his neck with a leather strap. He kept his fingernails long so that he could clip the cork pea between the nail and flesh of a finger as he supposedly set a cup down over it. This method was more difficult than the French “finger palm” more commonly used at the time.

In his first two months in Sacramento, Thornton made $24,000. He went broke several times with his addiction to Faro and profligate spending, but always made his fortune back with the help of the “three musketeers” and the little pea. He eventually established a ranch in the Carson Valley of Nevada near the town of Genoa that he stocked with several thousand head of cattle. He built a sawmill and operated a toll road, becoming one of the area’s most prosperous and respected settlers.

Thornton’s luck ran out when he was convicted of murder and cattle theft, and hanged on June 18, 1858.

William “Canada Bill” Jones (18??-1880)

William “Canada Bill” Jones

Canada Bill in his “hog drover” makeup

Canada Bill Jones was born in a gypsy tent in Yorkshire, England. He moved to Canada where he learned his trade from Dick Cady, a veteran three-card monte player. By the time he left Canada for the rich pickings in the pre-war South, Bill was an expert at the game. Two decades of experience on the southern rivers, and Canada Bill became the greatest monte sharp to ever “pitch the broads.”

“Canada Bill was a character one might travel the length and breadth of the land and never see his match, or run across his equal. Imagine a medium-sized, chicken-headed, tow-haired sort of a man with mild blue eyes, and a mouth nearly from ear to ear, who walked with a shuffling, half-apologetic sort of a gait, and who, when his countenance was in repose, resembled an idiot. For hours he would sit in his chair, twisting his hair in little ringlets. His clothes were always several sizes too large, and his face was as smooth as a woman’s and never had a particle of hair on it. Canada was a slick one. He had a squeaking, boyish voice, and awkward, gawky manners, and a way of asking fool questions and putting on a good natured sort of a grin, that led everybody to believe that he was the rankest kind of a sucker-the greenest sort of a country jake. Woe to the man who picked him up, though. ”

-George Devol, Forty Years a Gambler on the Mississippi

One of the most famous and most often quoted of all gambling stories, is about the time that Canada Bill had to spend the night in Baton Rouge, and searched all over town until he finally found a Faro game in the back room of a barbershop. George Devol found him there and saw immediately that the dealer was cheating using a “two-card” (rigged) box. He begged Bill to quit the game. “Can’t you see this game is crooked?” Devol asked. “Sure I know it, George,” sighed Bill with resignation, “but it’s the only game in town.” The punch line of this story has become a familiar part of our popular culture.

Canada Bill once wrote to the general superintendent of the Union Pacific Railroad. In his letter he offered $25,000 a year for the exclusive rights to run a three-card monte game on the trains. He promised to limit his victims to commercial travelers from Chicago and Methodist preachers. The railroad official politely declined the offer.

In the mid-seventies, as the railroads went the way of steamboats for the sharpers, Bill began a grand tour of racetracks around the country. He made so much money at monte and other swindles that he could have retired a dozen times. Unfortunately, Canada Bill couldn’t stay away from Faro and short cards. This ironically confirms Bill’s often quoted claim that “Suckers have no business with money, anyway.”

Canada Bill Jones died in 1880 in Reading, Pennsylvania. He was destitute, and buried at public expense. One of the gamblers who stood by as they lowered Canada Bill into the ground offered to bet $1000 at two to one odds that Bill wasn’t in the casket. There were no takers. One gambler within earshot said, “I’ve seen Bill get out of tighter holes than that before.

When the western gambling fraternity learned of his death, a group of them from Chicago raised money among themselves to recompense the city of Reading for the funeral expenses, and had a gravestone erected for Canada Bill. But Canada Bill’s real monument is his “rube act” creation-which proved so devastating a tool in the hands of the many sharpers who followed him.

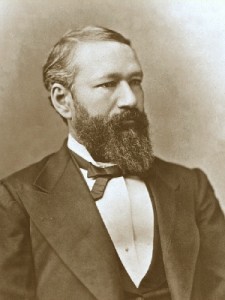

George Devol (1829-1903)

George Devol was born in 1829 in Ohio. He ran away from home at the age of ten as a cabin boy on a riverboat. After seeing the high lifestyle of the professional gamblers that steamed up and down the river, Devol devoted himself to the study of cheating. By the time Devol was in his teens, he could deal bottoms and seconds, palm cards, and recover the cut. He first made big money at the age of seventeen. It was the time of the Mexican War, and he trimmed soldiers on the Rio Grande.

He was a big man, weighing over two hundred pounds. He had a large head and big hands, and claimed that he could “hold one deck in the palm of my hand and shuffle up another.” Devol loved to fight, and often used his remarkably thick forehead to butt his opponents senseless. He never hesitated to pull a gun, accept a fair fight or-if necessary-run. Some of the exigencies of his profession are made clear in his autobiography as he explains:

“I don’t know (and I guess I never will while I’m alive) just how thick my old skull is, but I do know that it is pretty thick, or it would have been cracked many years ago, for I have been struck some terrible blows on my head with iron dray-pins, pokers, clubs, stone-coal, and bowlders, which would have split any man’s skull wide open unless it was pretty thick. Doctors have often told me that my skull was nearly an inch in thickness over my forehead.”

– -George Devol, Forty Years a Gambler on the Mississippi

George Devol made and spent many hundreds of thousands of dollars in the years preceding the Civil War, working mainly on steamboats in the South. His partners included Bill Rollins, Canada Bill Jones, Edward “Dad” Ryan, Big Alexander, Tom Brown, Posey Jeffers and Holly Chapell.

Devol headed west after the war and became part of the army of skin game artists working Hell-on-Wheels-the entertainment tents that followed the workers who laid the Union Pacific railway. Prostitution, gambling, variety entertainment and liquor were among the surest ways to make a lot of money quickly, but the sure-thing was surest of all. Sometimes the monte was played at a table in the gambling tents just like a casino game.

In the early 1870’s, Devol worked the trains between Cheyenne and Omaha, and between Omaha and Kansas City. His partners from the south were Canada Bill, Sherman Thurston, Jew Mose and Dad Ryan. They competed against, and sometimes teamed up with westerners like John Bull, Ben Marks, Cowboy Tripp, Doc Baggs, and Frank Tarbeaux.

George Devol and Jew Mose were working the Cheyenne to Omaha train when Devol picked up a man on the sleeper and beat him out of $1,200. It turned out that he was one of the directors of the road. As soon as he reached Omaha, the outraged official had handbills printed and hung up in the cars that not only prohibited gambling, but also threatened to fire any conductor permitting the game to take place on his train. The railroads sent in Pinkerton agents to watch for the best known of the fraternity.

The great days of the railroad gamblers were over. Devol quit the profession in 1886, at his new wife’s insistence. The last years of his life were spent peddling copies of his autobiography. During his forty years as a gambler he estimated he won over two million dollars. He died in Hot Springs, Arkansas in 1903, virtually penniless.

Pinckney “Pinch” Benton Stewart Pinchback (1837-1921)

Pinckney Benton Stewart Pinchback

Around 1850, Canada Bill and George Devol taught a young African-American boy named Pinchback to throw the monte. He had been working for Devol and his team as a body servant, and was known as “Pinch.” His real name was Pinckney Benton Stewart Pinchback, and he was born in Macon Georgia in 1837. Pinch’s father was a white planter and his mother a slave. The father freed the mother before the boy was born. When the planter died, the mother and her children moved to Ohio for fear that white relatives might try to put them back under slavery. Eventually, young Pinchback became a steward on the steamboats plying the Mississippi, Missouri and Red rivers. Pinch was an intelligent and charming boy who was shining shoes in a steamboat barbershop when Devol picked him up.

Devol and Canada Bill tutored Pinch on the intricacies of their trade, and soon while Devol and his partners were fleecing the white folks in the steamship’s saloon with monte, faro and poker; the boy was up on deck roping in the black deckhands with a chuck-a-luck game. In later years Pinch continued to do very well for himself, and used the money he saved from sure-thing gambling to finance a political career. Like Devol and the others, he quit the river soon after the Civil War began, and in 1862 he ran the Confederate blockade at Yazoo City, and reached New Orleans soon after the capture of the city by Farragut. He raised a company of black volunteers for the North, called the Corps d’Afrique. Much later, when he encountered racial discrimination in the service, he resigned his captain’s commission.

After the war, Pinchback immediately rose to a position of prominence among the blacks in New Orleans. He organized the Fourth Ward Republican Club and became a member of his party’s state committee. Thereafter, he was increasingly important in carpetbag affairs. In 1868 he was elected to the state Senate and in 1871 was chosen Lieutenant Governor to fill the vacancy occasioned by the death of Oscar J. Dunn. He was acting governor of Louisiana from December 9, 1872 to January 13, 1873, during the impeachment of Governor H. C. Warmoth. Later in the year 1873 Pinchback was elected to the United States Senate. The Senate, however, after three years of debate refused to seat him, supposedly because of voting irregularities but most probably because of race. Nevertheless, the Senate awarded him the pay and mileage of a senator for his term.

Pinchback never forgot his friends among the gamblers, and once, while occupying the governor’s chair, he was able to have George Devol as a guest at the Governor’s mansion and to help him out of a scrape. Pinchback used his position to quiet a New Orleans Police Commissioner whom Devol had beaten out of $800 playing three-card monte.

At the Constitutional Convention of 1879, Pinchback pushed for the creation of a college for blacks in Louisiana, thus helping to found Southern University. Pinchback and his family moved to New York where he was a Federal Marshal. At the age of 50 he decided to take up a new profession and entered Straight College, New Orleans, to study law. He was subsequently admitted to the bar.

Disillusioned with the outcome of Reconstruction and the return to power of the traditional white hierarchy, he moved to Washington, D.C., where he remained active in politics. There he took in his daughter and her son after her husband abandoned her. He helped raise his grandson, who became the celebrated idealist poet, philosopher and novelist Jean Toomer-one of the founders of the Harlem Renaissance. Pinchback died in 1921, and is buried in Metairie.

Charles “Doc” Baggs

Charles “Doc” Baggs

Baggs was one of “the sharpest of the sharp,” and became one of the most notorious con men in an era of fabulous skin-game artists. He graduated from monte steerer to full-fledged bunco operator. He claimed to have been arrested “about a thousand times,” but was never convicted of anything.

Once, when arrested by lawman Michael Spangler on a charge of “bunco-steering,” Doc acted as his own attorney. “Gentlemen,” he told the court, “no such term as ‘bunco-steerer’ appears in the statutes defining criminal acts. How could I possibly be guilty of a charge not prohibited by the statutes?” Doc Baggs even produced a huge dictionary, thumbed through it and then announced that it didn’t even contain the term. This completely baffled the court, and the judge dismissed the charge.

Baggs once declared, “I defy the newspapers to put their hands on a single man I ever beat that was not financially able to stand it. I am emotionally insane. When I see anyone looking in a jewelry store thinking how they would like to get away with the diamonds, an irresistible desire comes over me to skin them. I don’t drink, smoke, chew, or cheat poor people, I pay my debts.”

Doc Baggs was always among the best dressed of a fancy-dressing crowd. He never quarreled or used loud words. He was soft-voiced, gentle-mannered, and always wore a smile. He was a consummate actor, equally convincing as a ranchman, stockman, miner, banker, minister or laborer. Any theater property man would be proud to own a costume wardrobe as extensive as Doc’s vast array of disguises.

He is credited with inventing the “gold brick” confidence game, with which he managed to fleece many wealthy and prominent people. He extended and improved the concept of the monte store that was invented by his friend and fellow traveler Ben Marks-an invention that revolutionized con games and became the basis for the so-called “big store,” the foundation of all the big cons.

Benjamin “Ben” Marks

Benjamin “Ben” Marks

Benjamin Marks was born in Little Fort, Illinois (later renamed Waukegan) in 1848. At the age of thirteen he served as a dispatch bearer in the Civil War. During the year 1867, at the age of nineteen, he worked his way westward to Cheyenne, Wyoming, from a home in Council Bluffs, Iowa-dealing three-card monte on a board suspended from his shoulders.

Marks-like Doc Baggs, Canada Bill Jones, Frank Tarbeaux and the others with whom he teamed-called himself a gambler, but was in fact a confidence man. His object was to steer his victim into a trap, lead him to believe he was on the inside of a “sure thing,” and then milk him dry.

But in Cheyenne, during the days of the Hell-on-Wheels horde, he found the competition in the gambling tents too tough. He hit upon an idea that, according to Maurer, was “to revolutionize the grift, an idea which was to become the backbone of all big-time confidence games.”

Ben Marks posted a sign on a Cheyenne building reading, “The Dollar Store.” The store’s window exhibited all sorts of goods, each item worth much more than a dollar. Inside, Marks and his cohorts would wait. Bargain hunters and “something-for-nothing chumps” soon appeared.

Once inside, the sucker’s interest was switched from the dollar bargains to a three-card monte game being dealt on a wooden barrel. Since no customer ever left the monte game with any money in his pocket, none of the merchandise was ever sold.

Ben Marks had considerable success in his various con games, but was later in life to become an excellent businessman. He was considered a political heavy, a man who could make or break a man politically. He was well-respected as a “gambler and philosopher, and a good judge of men, land and horses.”

Marks, like Tarbeaux said of his gambling cronies, was a “pretty hard baby.” According to W.R. Mynster, Council Bluffs ministers prone to sermons about prostitution, temperance and gambling, would get a kindly visit from Ben who would give them a long talking-to with occasional quotes from the scripture and one assumes liberal financial contributions. On occasion, he offered more tough stuff.

With “plain or garden reformers,” Marks recommended that the aggrieved go to the office of the reformer “.and be sure you are alone. Then tell him that you are sorry he is acting the way he is, and if he acts different it will be to his advantage-if not it’s apt to cause a lot of trouble. If he gets big and blustery, just get up and go over and shove a gun in his ribs. Then tell him in plainer and more forceful language. Promise to come back if necessary, and if he has been a sinner tell him about it. Be convincing, and prod him a bit with the barrel.”

Ben and Mary had a big three-story log farmhouse in Elks Grove just outside of Council Bluffs straddling the county line. The “Hog Ranch,” as it was called, was not only their home but a well-known and popular casino and brothel-Mary was a successful madam and considerable character in her own right. The law officers of one county would raid the place to find everyone had moved to the other end of the room-across county lines and out of jurisdiction. This house still stands outside of town.

When he died, Marks had extensive properties of farmland in South Dakota, Iowa and Nebraska. Like Doc Baggs and Frank Tarbeaux, he was one of the rare success stories in the con game business who did not throw everything away through high-living and gambling. Ben Marks and his wife Mary lived near Council Bluffs, Iowa until his death from liver failure in 1918. He was seventy-one years old.

David Maurer writes about Ben Marks’ contribution: “Thus, in a very crude form, developed what we know today as the ‘big store’-the swanky gambling club or fake brokerage establishment in which the modern payoff or rag is played.” The movie The Sting was based on this sort of “big store” con. Doc Baggs took the store concept to great heights.

Frank Tarbeaux

Frank Tarbeaux was born at the site of present day Boulder, Colorado in 1852. He claimed to be the first white child born in Colorado. Young Frank fought Indians “before his voice changed” and killed his first man when only fourteen. He was making his way as a professional gambler by the age of eighteen. He worked the trains out of Omaha doing Canada Bill’s “rube act” when he was still in his early twenties.

Tarbeaux was the very model of the western gambler, and in fact, Sir Gilbert Parker and Frank Harris both wrote fictional works that were based on the character that they each had met in real life-Frank Tarbeaux:

A striking, clean-shaven, good-looking man whose years it would be impossible to say, for he had no gray hair, and yet there was a look, not of age, but of long experience, in his face.It was a figure and a face not to be forgotten. There was a touch of the foreigner in his looks and yet he did not speak with an accent.It was a face that never wrinkled with emotion. Its only life was in the eyes and at the mouth and they were most expressive. He had the impassive look of a Jap and was vigilant in a curious, quiet way.It was to be said that he had not had complete social training, and yet he was well dressed and had dignity. I can say truthfully I never met a man with greater social gifts, although it was clear he had limited education.His charm lay in keen intelligence, a rare natural philosophy, and in humour of an original kind.

-Sir Gilbert Parker, Tarboe, the Story of a Life

During his long life, Tarbeaux traveled extensively outside the United States, and claimed to have befriended many famous people including King Kalakaua of Hawaii, Oscar Wilde and Hadden Chambers. When he was seventy-seven in 1930, he gave his recollections to Donald Henderson Clarke and these were recorded in the book, The Autobiography of Frank Tarbeaux .

In this book Tarbeaux gives a detailed description of the rube act he used to perform on the trains. This description appears in our book The School for Scoundrels Notes on Three-Card Monte .

Clarke described Tarbeaux as he was in his late seventies: “This amazing man still dresses like a beau, rides like a hero, and shoots like a demon. Doctors have told him that his physical condition is perfect.”

Tarbeaux was one of the few really successful sharpers to retire comfortably and in good health.

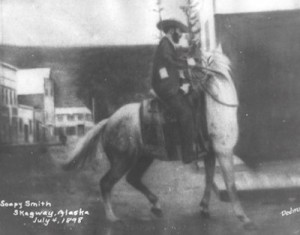

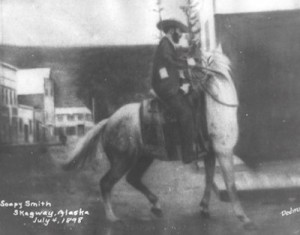

Jefferson Randolph “Soapy” Smith (1860-1898)

Jeff Smith first learned the shell game from a circus grifter named Clubfoot Hall, but his short and notorious career really took off in 1885 in Leadville, Colorado. There he apprenticed to “Old Man” Taylor, the foremost shell game operator of the day. Taylor was an expert pitchman, and the inventor of the soap swindle from which Jefferson Randolph Smith would get the nickname that would stick with him the rest of his life.

In the soap swindle, Soapy would present himself as a “soap salesman” on a city street corner. After extolling the many virtues of his wonderful soap, Sapolion, “made in my own laboratory from a secret formula,” a number of bars of soap were unwrapped in front of the public, and then folded back up with $10, $20 and $50 dollar bills hidden in the paper wrappers. These were dropped into a suitcase with the ordinary soap bars (worth about a nickel), and the spectators were allowed to take their pick at $5.00 a bar. Only the five or six shills in the crowd ever seemed to find any money since Soapy had palmed off each bill in the act of folding the wrapper.

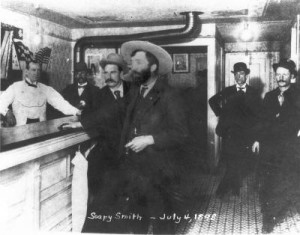

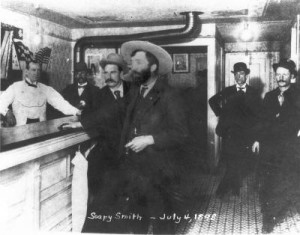

“Soapy” Smith’s Gang

Soapy Smith would become one of the most famous and influential con men of the nineteenth century. He even coined the term “sure-thing” bet. Eventually Smith would take over the vice and gambling in whole towns-in Denver and Creede in Colorado, and later in Skagway, Alaska. Doc Baggs and George Devol would steer for Soapy for a time, but Soapy’s main operating principle was the opposite of Baggs, Devol, and all those of the earlier period.

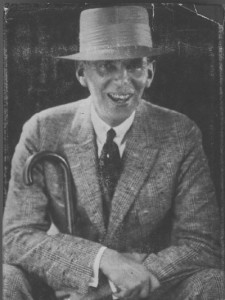

Jeff “Soapy” Smith

Jeff Smith and members of his gang

(Photos used with permission Dedman Photos, Scagway, AK)

Instead of finding the richest victim and taking him for the most possible, Soapy liked to take average people for less money. He planned to make it up in volume. By lowering his profile in this way, he could work the same area for a long time, and didn’t have to constantly “hit the road.” He believed in organization, and wanted all the grifters in an area working together. This would be useful in dealing with the authorities, many of who were already used to “arrangements” with various types of criminal gangs. He wanted to have the “fix” put in with the police, and if he didn’t bother the local people, and avoided violence this was usually possible-for a price.

Soapy was an expert at calling and holding a crowd on the street, and at the patent medicine show technique of filling the crowd with shills and boosters. He combined all the best methods of the street pitchman and medicine show with the con-artistry of the shell game.

Members of Soapy’s Gang

Citizen-vigilante Frank Reid and Jefferson Randolph Smith shot and killed each other on the Skagway docks in 1898. Soapy’s gang fled in every direction. It is certain that these talented and finely-trained con men carried on with his ideas as they scattered all across the country:

“The way of the transgressor is hard-to quit.”

-Jefferson Randolph “Soapy” Smith

Claude Alexander Conlin (1878-1954)

Poster of Claude Alexander Conlin’s Psychic Show

Claude Alexander Conlin was a young man in Skagway, Alaska during the Gold Rush when he was taken for every penny he had by Soapy Smith in the Shell Game. Soapy took pity on him and made him a member of his gang, putting him in charge of managing Smith’s prostitutes. His brief sojourn with the Smith gang gave him a lifetime of education in the art of the confidence man. Some evidence indicates that it was Conlin who fired the fatal shot that ended Soapy’s career. As Soapy and Frank Reid struggled on the wharf, Conlin fired the shot that killed Soapy according to John Pomeroy, a historian and researcher into the life of Alexander. This may have been in an attempt to protect the life of Conlin’s friend Alexander Pantages (founder of the Pantages theater chain) whom Soapy had threatened.

Conlin went on to become a vaudeville sensation as “Alexander The Man Who Knows” a psychic reader who set box-office records across the United States and amassed a fortune in the 1920’s estimated to be worth over $4 million dollars.

“Off stage, he was a charming, charismatic charlatan with an insatiable sexual appetite, who held an almost Svengali-like power over women. He was also an extortionist, bootlegger, and murderer who was both feared and hated by anyone whom he crossed.”

–David Charvet, Magic Magazine, June 2002

Wilson Mizner (1876-1933)

Wilson Mizner was another successful graduate of Soapy Smith’s own school for scoundrels in Skagway. He worked as one of Soapy’s lieutenants until Soapy was killed. One of his scams included working as a gold weigher in a dance hall. While balancing the scales, Wilson would spill gold dust onto a carpet. At the end of the week Wilson burned the carpet then extracted the gold from the ashes. In a 1905 interview, Wilson claimed that this trick resulted in a weekly yield of a couple of thousand dollars.

In “Schemers, Scalawags and Scoundrels”, author Stuart B. McIver relates one quasi-comic episode in the Yukon: “In the gold rush days in Nome, Alaska, [Wilson Mizner] put on a black mask, armed himself with a revolver and entered a candy store, shouting, “Your chocolates or your life!” Though the local sheriff knew Wilson was the culprit, there was no arrest. Later he was named as a deputy sheriff!

In 1905, Wilson showed up at a horse show where his brother Addison was ensconced in a pricey box with wealthy widow Mary Adelaide Yerkes. Addison pretended not to see Wilson, but the younger brother charmed his way into the box. Thereafter, Wilson worked speedily. He spent the night with Mrs. Yerkes, reportedly borrowing $10,000 the next morning.

Within a short time the 29-year-old, penniless Wilson and the 80-year-old Mrs. Yerkes were fodder for New York’s tabloids, the two having quickly married and just as hastily divorced. Wilson’s rakish lifestyle, however, soon made him a New York celebrity. He managed the Rand Hotel, one of the city’s most notorious canvasaries. “Guests must carry out their own dead” exhorted a sign prominently posted by Wilson. After designing the Rand’s elaborate bar, Addison receded into the background, his lack of a formal education in architecture hindering his aspirations to design buildings for New York’s wealthy.

Wilson’s career as a hotel manager soon ended and the snappily dressed, witty Runyonesque Wilson managed boxers, working in cahoots with New York underworld’s to fix the outcome of prize fights. (Wilson’s love of boxing stemmed from his youthful days in Benicia, California, where the Mizner family home was a hangout for San Francisco sportsmen. Before arriving in New York, Wilson managed fighters in Nome and Dawson and on tours of Western towns.) In New York Wilson managed, then famous, Stanley Ketchel, whose violent death occasioned one of Wilson’s more memorable quips: “Tell ’em to start counting ten over him, and he’ll get up.”

Wilson’s chums in New York included actress Marie Dressler (who later helped the Mizners sell real estate in Florida and who won an Academy Award for Best Actress in 1931). Another of Wilson’s New York contemporaries: Ben Hecht, who also helped the Mizners promote Florida real estate and who became a famous Hollywood screenplay writer.

Irving Berlin was an even better-known New York pal. At various times in his long career Berlin tried to write a musical based on Wilson’s life. “Unsung Irving Berlin”, a recently released CD, includes several songs composed by Berlin for his musical, known at various times as “Wise Guy”, “Sentimental Guy”, and “The Mizner Story”.

Perhaps Wilson’s greatest achievement in New York was the co-writing of his Broadway plays including The Deep Purple which opened in 1910 and which was lauded by a Chicago critic as “the greatest melodrama since Sweeney Todd’ (much later of course, Sondheim adapted the Sweeney story for the musical stage.) The New York critics weren’t nearly as enthusiastic as their Chicago counterpart about Wilson’s depiction of the seamier aspects of life, as depicted in The Deep Purple, The Greyhound and other plays.

Withal, Wilson’s career as a playwright was doomed by his laziness and by an increasingly severe addiction to opium. After being beaten up and left for dead in a New York alley, Wilson was given morphine to ease the pain in his broken jaw. Wilson soon became addicted to this strong drug.

Meantime, depressed by his lack of success in New York and by health problems, Addison fled to Palm Beach, where the Florida land boom was about to erupt. Alarmed by news of Wilson’s addiction to morphine, Addison brought Wilson to Palm Beach where Wilson managed to kick his habit. Wilson became Addison’s partner, raking in millions during the Florida land boom. When the boom crashed, however, Wilson abandoned Addison. The callous Wilson sped away to Hollywood, leaving behind the ailing, impoverished Addison.

Backed by movie mogul Jack Warner and actress Gloria Swanson (or possibly by one of Swanson’s former husbands), Wilson opened the Brown Derby restaurant, a hangout for moviedom’s most glamorous names. Wilson regularly held court from one of the Brown Derby’s booths, where his coterie included writer Anita Loos, who described Wilson as “America’s most fascinating outlaw”. Best known for writing “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes”, Loos also wrote the script for the film “San Francisco.” Loos reportedly based the film’s leading character in the movie “San Francisco” on Wilson (Clark Gable portrayed this film character).

Another Brown Derby habitue: Irving Berlin, a chum of Wilson’s during the Mizners’ sojourns in New York and Palm Beach. Once, Wilson had to be physically restrained after attacking a Brown Derby patron who Wilson thought had insulted Berlin. (Such episodes no doubt aggravated Wilson’s steadily worsening heart condition.) When not hanging out at the Brown Derby, Wilson was most often on the Warner Brothers lot, where he was hired as a scriptwriter. Though touted for his screenplay for “One Way Passage, an early talkie hit, most of Wilson’s time at Warner Brothers was spent loafing.

Occasionally, friends from Wilson’s earlier years would show up at Warner Brothers. In New York, Wilson managed a middleweight fighter, Stanley Ketchel, who lasted 12 rounds against heavyweight Jack Johnson. Two decades later, Johnson was hired for a bit part in a Warner Brothers movie. Wilson took the former boxer around the lot, introducing him to the top brass at Warner Brothers.

The ever-cynical Wilson characterized his Hollywood years as “a trip through a sewer in a glass-bottomed boat.” Wilson had taken a few such trips. This time there was a difference: Addison Mizner was no longer a co-passenger.

Throughout his life, Wilson mocked death. Whilst living in Palm Beach, Addison delivered somber news to Wilson. Another Mizner brother, Lansing, was killed in a traffic accident. Wilson’s reaction: “Why didn’t you tell me before I put on red tie.” Following a quarrel with Wilson, a young woman committed suicide by jumping from the 11th floor of a hotel in Palm Beach. Again, Addison bore the bad news to Wilson, who immediately headed toward the door. “I’m going to place a bet on No. 11. You can’t tell me this isn’t a hunch.”

Whilst writing a screenplay in early 1933, Wilson learned that the destitute Addison was gravely ill. “STOP DYING,” Wilson cabled. “AM TRYING TO WRITE A COMEDY.” Shortly after Addison died, Wilson had a heart attack at the Warner studio. Asked if he wanted a priest, Wilson delivered another of his memorable lines. “I want a priest, a rabbi, and Protestant clergyman. I want to hedge my bets.” As an oxygen tent was placed over Wilson’s bed, he said “It looks like the main event.” A priest reminded Mizner that death could come at any moment. Wilson’s classic response: “What? No two weeks’ notice?”

“Cracker” Parker

Cracker Parker

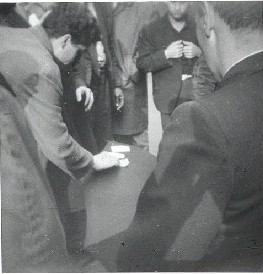

Polish Kilczynski

throwing three-card monte in London 1954.(photo by Ron Wohl)

“Cracker” Parker ran one of the most sophisticated three-card monte gangs ever in the Tottenham Court area of London. He would operate six or seven different teams in the area, training, equipping and managing all of them for more than thirty years (1950’s-1970’s). Parker was Australian born, but grew up in London. His childhood friends included Ronnie Biggs and Buster Edwards who later became famous for their part in the “Great Train Robbery” of 1963.

“Polish” Kilczynski was a dealer and close friend of Parker’s. Gazzo worked with this gang in the seventies when he was a teenager, and he describes their methods and subterfuges in the School for Scoundrels Notes on Three-Card Monte .

Other important scoundrels:

Dick Cady

Nutshell Bob

Yankee Hank Fewclothes

“Sure-Shot” Tom Cady

John Ashby

Frank Tarbeaux

Posey Jeffers

Pinkney Benton

Stewart “Pinch” Pinchback

Jackson “Rattlesnake Jack” McGee

John Bull

Clay Wilson

Charley Bush

Jew Mose

High Miller

Jim Moon

Poker Davis

Banjo Parker

“Icebox” Murphy

King Warren

Bat Masterson

Wyatt Earp

Tex Rickard

“The Reverend” Charles Bowers

Edward “Dad” Ryan

Mason Long

Ephraim “Eph” Holland

Bill Rollins

Big Alexander

Bill Simon

Tom Brown

Holly Chapell

Cowboy Tripp

Bob Ford

“Eat-Em-Up Jack” Blackburn

“Swiftwater” Bill Gates

Jim Thornton

For more information on these and other scoundrels and the history of sure-thing swindles, see The School for Scoundrels DVD on Three-Card Monte and The School for Scoundrels Notes on Three-Card Monte

Looking for capable help…

We are always on the lookout for photos, historical information, technical tips, etc. on short cons and con men from our friends, fans, and fellow travelers…